On the 23 to 25 August 2017, an online auction was held by John Hume, for 264 lots (approximately 500kg) of rhino horn from his private stockpile of some 6 tonnes. The online auction was not a great success apparently.

The next Hume led ‘physical’ rhino horn auction is due in South Africa around the 19 September 2017 (or perhaps in the “……next two or three months“). But, perhaps the Republic of South Africa, Department: Environmental Affairs (DEA) has sought to delay proceedings to ensure some semblance of compliance is even possible as verification of private rhino horn stockpiles is still ongoing – according to notes from the Republic of South Africa’s Cabinet meeting (dated 30 August 2017):

“Cabinet welcomes the announcement from the Minister of Environmental Affairs, Ms Edna Molewa that South Africa is finalizing in the outstanding three provinces, a verification and audits of all the existing privately owned rhino horn stockpiles.

The initial audit which was conducted by the provinces is being checked and verified by the national Department of Environmental Affairs” – All Africa, 30 August 2017

However, the principal questions that still remain unclear are:

- How does the ‘domestic’ rhino horn auctions (and calls for international trade) held by John Hume (supported by the Private Rhino Owners’ Association (PROA)) fit with any feasible, overall strategy to help the rhino species survive in the wild?

- Is the Republic of South Africa, Department: Environmental Affairs (DEA) strategy still to seek CITES approval for the lifting of the international ban on rhino horn trading at CoP18? Note: South Africa withdrew its proposal for such international ‘trade’ at CoP17, Sept – Oct 2016 – Swaziland’s proposal to CoP17 for international rhino horn trade was defeated by 100 against, 26 in favour, with 17 abstentions.

The Hume/PROA ‘Strategy’

What is the strategy and scientific backing for the Hume/PROA’s suggested liberation of domestic and international rhino horn trading? The stated aim is to ‘compete’ with incumbent criminal networks that supply poached rhino horn (plus the scourge of pseudo- rhino hunting, which has been used in the past to ‘legally’ obtain rhino horn for use in Asian markets).

So how does one ‘compete’ in a market with the current, incumbent illicit supply?:

- Price

- Demand

- Markets

Price

One driver promoted by the private rhino owners in favour of selling rhino horn internationally, is the rhino owners’ ‘belief’ that supplying the market with legal horn will undercut poachers, who sell rhino horn on the black market for “astronomical prices” ($60,000/kg or more). This undercutting on price, argue the private rhino owners, would cripple the poachers’ operations. But this ‘belief’ is contradicted by recent experience within the market for ivory.

The recent clampdown on ivory carving factories in China has significantly lowered the price demanded for ivory, but the pressure applied to the criminal syndicates’ margins has not fully crushed on-going poaching of wild elephants to still profit from demand and speculative stockpiling:

“Even with the price coming down, there’s still a heck of a lot of poaching going on,” Douglas-Hamilton (Save the Elephants) said. “It’s important prices have come down but it hasn’t killed the trade, we’re not out of the woods yet” –Story behind China ivory ban, The Guradian, 29 August 2017

What is to say that the incumbent criminal syndicates will not increase volume to make up for any short-fall in margins realised?

The assumption in the Hume strategy that price is key, is not supported by economic modelling of the market dynamics:

“The system dynamics model we developed, indicates that demand is not sensitive to changes in the price of rhino horn. This is consistent with the observations of Milner-Gulland (1993). The implication of this is that lifting the trade ban, even if it results in a reduction in rhino horn price, will not alleviate demand” – “Debunking the myth that a legal trade will solve the rhino horn crisis: A system dynamics model for market demand,” Economic Research Southern Africa (ERSA), D. J. Crooks and J. N. Bilgnault, Journal for Nature Conservation, Elsevier, Pretoria, 2015

But, reducing price can/will increase demand, as rhino horn could potentially become more affordable to a previously economically excluded market element and short-cut the rhino to extinction:

“…..if more legal horn goes on the market not only in SA but in Vietnam and China it would create a niche for people who, in the past, could not afford rhino horn being sold by black-market dealers. Not only are you increasing the market base in countries that consume the horn but you will make it more affordable, which means the demand for rhino horn is going to go up…. the risk is that if demand increases as more people buy rhino horn and legal trade fails to meet the demand, poaching will spike. Countries with smaller populations of wild rhino will be hardest-hit as they don’t have the resources to defend their herds” – “The economics of rhino horns,” Business Live, 31 August 2017 – Joseph Okori, the Southern Africa Director of the International Fund for Animal Welfare

“If there’s increased rhino poaching following trade legalization, even for a brief period and at a relatively low level compared with the present, this could be catastrophic for rhinos” – “Legalizing Rhino Horn Trade Won’t Save Species, Ecologist Argues,” K. Nowak, National Geographic, 8 January 2015

Demand

The demand curve for rhino horn is potentially massive compared with availability to supply rhino horn from wild and private rhino:

Private rhino horn supply/stockpiles are unable to meet even a mere fraction of the potential peak demand – The South African government’s 25 tonnes (worth approximately $750m USD) and John Hume’s 6 tonnes (worth approximately $180m USD) stockpiles would supply 50g of rhino horn to a mere 620,000 people, or some 0.042% of the total current population of China and Vietnam of 1.45bn – “South Africa’s claimed need for wildlife utilisation,” IWB, July 2017

“These simple calculations support the notion that lifting the ban on commercial trade in rhino horn is likely to facilitate the extinction of rhinos, rather than support their survival. Illegal rhino horn trade is an international problem that requires a well-coordinated global response comprising a genuine commitment to strong legislation, uncompromising enforcement and creative demand reduction initiatives” – “A quantitative assessment of supply and demand in rhino horn and a case against trade,” NABU International, Barbara Maas, Berlin, 2016

As stated above, there is no rule that says poachers will not increase volume (ie. poaching more rhino) in an effort to ‘compete’ on price and maintain nett profits from their illicit trade.

Dr George Hughes (zoologist and former game ranger, who rose through the ranks to become chief executive of the renowned Natal Parks Board) has come out in support of Hume in a recent article:

“South Africa’s current rhino conservation strategies were indefensible and financially unsustainable” he said noting that South Africa had lost more rhinos to poachers in the last six years than over the past 50 years. “You can’t expect farmers to put in a huge amount of money that is not going to give them a return on investment. (Wildlife ranching) is a perfectly legitimate business that has been going on for decades” – “Rhino baron should be hailed, not pilloried says former parks boss,” Times Live, 30 August 2017

Dr George Hughes argues that ostrich and springbok are farmed, so why not rhino?……Of course, except the examples given of ostrich and springbok are bred for game/meat and these are not endangered species. Rhino are bred for highly over-priced medicine (no efficacy), status symbols and speculative investment (based upon the rhino’s extinction) – so there’s no actual read-across whatsoever to ostrich, springbok etc.

Albina Hume states “Here’s a few species that come to my memory: white rhino, vicuña, crocodile, bison, a few gazelle species, ostrich” – David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation

However, vicuña were only imperilled after sustainable subsistence trading was introduced (1990 – 2000s) in the vicuña’s harvested fur, so the vicuña as a species was not enhanced by ‘utilisation’ and ‘trade’ which encouraged poaching to profit from the stimulation in demand, threatened those communities that were supposed to profit from the trade and led to thousands of vicuña being slaughtered. Many scientists are concerned that the vicuñas’ population levels remain of concern:

“….but most experts agree that there is cause for concern. Vicuña populations now hover at 400,000 to 500,000 animals, but their numbers have remained stagnant or, in the case of Chile, declined over the past two decades” – “Poaching upsurge threatens south America’s iconic vicuña,” Scientific American, 24 November 2015

Markets

“As custodian of the overwhelming majority of the world’s remaining rhino population, Hughes maintained that South Africa should simply notify other member states of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) that it intended to resume trading rhino horn internationally.”It should be a no-brainer to show that sustainable use of wildlife has been phenomenally successful in South Africa. Our tourism industry is worth billions and that there is nothing wrong with rhino farming” – “Rhino baron should be hailed not pilloried says former parks boss,” Times Live, 30 August 2017

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES)

So, according to Dr George Hughes, the international community represented by CITES should be ignored if the 183 Parties to CITES cannot be relied upon to sanction international trade in rhino horn at the next Conference of the Parties (CoP18).

What sort of international message of unity does that send, if the global acceptance for such a plan can be overridden in the interest of the self-interest of one Party to CITES? CITES may not be an effective force for conservation, but what would stop CITES’ disintegration if South Africa decided to take unilateral action? Most likely it would trigger other Parties to follow suit and self-declared open warfare on all species (in the name of profiteering).

Sustainable use of wildlife

Dr George Hughes also states that “sustainable use of wildlife has been phenomenally successful in South Africa.” One only has to look at the ‘canned’/’captive’ big cat industry in South Africa to counter that delusion:

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) concluded in September 2016:

“…the prohibition by the South African Government on the capture of wild lions for breeding or keeping in captivity” and “terminating the hunting of captive-bred lions (Panthera leo) and other predators and captive breeding for commercial, non-conservation purposes.”

The South African ‘captive’ lion skeleton exports and quota lacks any obvious, independent (peer reviewed) scientific credibility.

Maltreated ‘captive’ lions – Walter Slippers’ ‘ranch’, July 2016

Lest we forget the maltreated big cats held within South Africa’s captive industry, what is to say any potential bonanza in rhino breeders seeking to maximise profiteering for a legal, international trade in rhino horn will not encourage similar depraved animal welfare to proliferate? The ‘legal’ trophy hunting of rhino within South Africa led to the scourge of “pseudo hunting“ by Vietnamese posing as hunters, where the driving force was to obtain rhino horn by deception (and was happily facilitated by ‘professional’ hunting outfitters). It took over seven years to address the issue of “pseudo hunting,” but this has since morphed into on-going deceit, as third party nationals cover the true intent of rhino trophy hunting and intent to obtain rhino horn within Vietnam.

“Since 2003, wildlife crime syndicates have sought to exploit legal trophy hunts of white rhino in South Africa as a means of obtaining horn for Asia’s illegal black markets. Known as “pseudo-hunting”, the fraudulent practise became so widespread by 2010 and 2011 that sham ‘hunters’ recruited by wildlife trafficking syndicates in Vietnam, Thailand, South Africa and the Czech Republic accounted for the vast majority of white rhino hunts in South Africa” – “Tipping Point – The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime,” (page 35), Part 1, July 2016

The DEA’s draft ‘domestic’ rhino horn trade regulations made provision for private rhino ownership within South Africa as a means to obtain permits for a given rhino’s harvested horn – what’s to stop the proliferation of “pseudo rhino ownership” as an ongoing deceit in a rotating rhino ownership deception to obtain rhino horn (that magically gets spirited out of the country by convenient onward actions)?

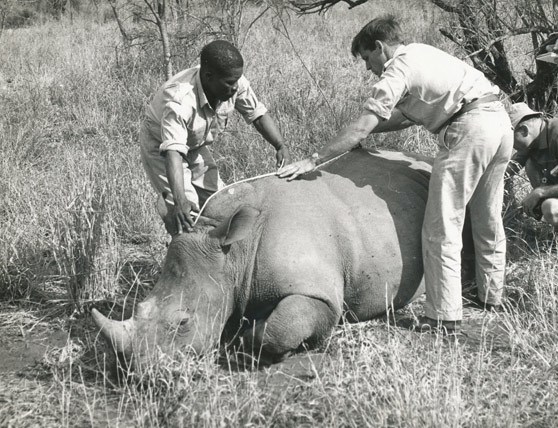

The pro-trade/wildlife utilisation lobby will of course refer to ‘Operation Rhino‘ as the leading example of “success” (an example from the 1960’s duly noted):

“The project aimed to increase the rhino population by moving some of the last remaining rhinos to game reserves across SA and the rest of the continent. Another contributing factor to this rise in the rhino population in South Africa was the fact that trophy hunting of the species was banned” – “Who’s actually killing and making a killing from rhino,” IWB, 16 April 2016

However, it must also be noted that ‘utilisation’ (including hunting) led to the rhino’s dilemma and near extinction in the first place:

“In the year 1800 about 1 million rhinos lived on earth…Rapid human population growth and more efficient hunting methods greatly accelerated the decline of rhinos during the 1800s and 1900s” – ‘t Sas-Rolfes, Michael “Saving Rhinos: Success versus Failure,” Rhino Economics, 2011.

“Hunters claim to have increased wildlife numbers from the point where some species (like rhino) were at risk of extinction. They lie. First, it was the hunting fraternity itself that wiped out our wildlife, bringing game numbers to an alarming low point. So now the hunters want credit for saving animals from themselves. A typical extortion racket!” – Chris Mercer (CACH), 13 April 2016

Albina Hume argues “....which species has got extinct or is threatened to extinction because of the CITES legalization of trade in their products?” – David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation

Sustainable use of wildlife in South Africa may have been phenomenally successful in creating income for some perhaps, but in many cases it has no moral, ethical or conservation merit whatsoever. Past and present trade (trophy hunting, body parts etc.) has failed lions, tigers, elephants, leopards……..all are on the decline to extinction in the wild across past ranges unless there is a turnaround. The proof of the “success” of wildlife utilisation is not when it fails to take a target species to the brink of extinction, if the true intent in such ‘utilisation’ is the stated conservation of the species and not just the income that can be derived from the trade/utilisation.

Perhaps the principal problem with the biased adoption by some of ‘sustainable utilisation’ as the only solution is the notion that it’s justified regardless of any imposing law. Modern-day game farmers are a powerful commercial and political lobby, that perhaps hold more sway over the future of wild rhino than the Republic of South Africa’s own DEA, and do not see acting on the periphery of legality as ‘criminal:’

“The notion of ‘contested legality’ was introduced as a legitimation strategy of important actors who justify their participation in illegal or grey flows of rhino horn based on the perceived illegitimacy of the rhino horn prohibition” – “A Game of Horns“ (page 366), Annette Michaela Hubschle, International Marx Plank Research School on the Social and Political Constitution of the Economy (IMPRS SPCE), Köln, Germany, 2016

Does game ranching make a positive contribution to conservation? A 2016 paper, “The Conservation Cost of Game Ranching,” demonstrates that there are serious concerns:

“…..that game rancher tolerance towards free-ranging wildlife [particularly leopard] has significantly decreased as the game ranching industry has evolved. Our findings reveal a conflict of interest between wealth and wildlife conservation resulting from local decision making in the absence of adequate centralized governance and evidence-based best practice. As a fundamental pillar of devolution-based natural resource management, game ranching proves an important mechanism for economic growth, albeit at a significant cost to conservation.”

In summary, “sustainable utilisation of wildlife” is not the panacea some try to claim it to be.

Demand Reduction

“Finally, it’s time to recognize a fact that it’s not the demand for rhino horn that is killing the rhino, but the method by which such demand is supplied! I am highly supportive of demand reduction programs but in the same manner is [sic] it’s done for demand reduction for the use of sugar, alcohol or cigarets [sic] – without outlawing trade in these products! Education should be about a freedom of choice, not a blatant prohibition”- Albina Hume, David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation

Not sure what the first part of Albina’s ‘strategy’ means – but if it’s not demand driving rhino poaching, then what is? Any ‘belief’ that the method by which demand can be supplied can simply be switched from incumbent criminal and illicit networks is something of a fantasy. The pro-trade ‘belief’ that the criminal networks will fold-up because the price of rhino horn has dropped due to alternative sources is not borne out by the current experience with ivory or academic studies.

Not sure how anyone can be highly supportive of demand reduction, but at the same time seek to supply that demand?

In a 2016 paper “To stop poaching, ivory ban must be permanent,” Ross Harvey (MPhil) demonstrates via game theory modelling, that to end poaching to meet any sustained demand, bans must be all encompassing and permanent. Any hint, or tacit acceptance that trade (which includes obtaining rhino horn via trophy hunting for example) will be tolerated and resume at some future point only invites ongoing stockpiling and speculation, which in turn continues to drive poaching seeking to profit.

In addition, from a demand perspective for wildlife products, there has been debate over whether the end user demands a specific supply, wild vs. ‘captive’ grown rhino horn for example.

Breaking the Brand, Third Annual Report, 2017

There is more than anecdotal evidence (Breaking the Brand, page 25) that suggests the preference is for wild sourced product. But, to my mind, the whole demand/supply is based on fraudulent claims such as unproven medical efficacy. As with South Africa’s lion bones exported as a substitute for tiger bones, the end user is commonly none the wiser what they are buying and its true source – again, fraud/deceit is prevalent in the wildlife ‘utilisation’ industry’s supply to meet demand.

In summary, to be successful, demand reduction cannot be half-hearted, circumvented and/or blended with any means of supply. If the true intent is to stop poaching, then demand reduction must be absolute.

Prohibition

Any prohibition, or restricted market access to “sugar, alcohol, or cigarettes” is based upon commodities that have no read-across to the ‘utilisation’ or risk of extinction of a wildlife species. If the pro-trade advocates get their way and international trade in rhino horn is given unlimited approval, the risk is that demand can easily be stimulated to outstrip supply – and that is not an excess demand based upon a lack of sugar cane, distilled alcohol ingredients or tobacco plants, but the extinction of a wildlife species. As far as I am aware, no one has, or is currently speculating on the impending extinction of sugar, alcohol, or tobacco, but there are those speculating upon the extinction of the rhino by investing in rhino horn. So, the market forces for the ‘commodities’ cited within the Hume strategy are not comparable to rhino (or any other so threatened species).

Conclusions

There has been widespread negative reaction (outside of the cartel of wildlife utilisation profiteers) to the opening up of a ‘domestic’ trade in rhino horn and the pro-trade lobby calling for international trade to be liberated. There is no independent, peer reviewed science that says such actions are likely to have anything but negative consequences for wild rhino conservation.

The Hume/PROA theories are based on simplistic economic assumptions that pricing is key, are not borne out by the experience with ivory or academic studies. Any pro-trade claims that ‘prohibition’ of alcohol etc. has any relevance to give weight to their arguments seems (at best) facile.

The ‘hope’ that incumbent criminal networks and complicit authority official will be scared off by ‘legal’ market interventions seems (at best) naïve.

There is no published Hume/PROA strategy on how any promised income from ‘legal’ rhino horn trade will protect rhino species world-wide. There might be self-proclaimed rhino custodians interested in securing their own private rhino and income stream, but what about the potential, negative global impact?

“This is something that’s happening for rhinos and elephants and other wildlife in Africa and presents a major challenge to “sustainable use” that is, you can’t guarantee that by starting a program of trade in a place where the animal is in abundance, you won’t drive the animal to extinction through illegal use where they’re still in danger” – “Legalizing Rhino Horn Trade Won’t Save Species, Ecologist Argues,” K. Nowak, National Geographic, 8 January 2015

The best hope remains law enforcement and demand reduction (as advocated by “Tipping Point – The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime“). The notion that a demand reduction message can be combined with sustaining supply from other means, again seems at best naïve.

What is the DEA’s perspective? I fear it remains pro-trade once private and in-house rhino horn stockpiles are sufficiently aligned.

In 2014, the DEA recommended in “The viability of legalising trade in rhino horn in South Africa” and will no doubt make an approach to CITES for CoP18:

“Taking into account the facts that the mechanisms for controlling a legal trade in South Africa are not yet in place, that the number of rhino horns in private stockpiles are uncertain, and that some private rhino owners are not yet compliant with permitting regulations, it is likely that lifting the moratorium at the present time will lead to laundering of illegal horn into legal stockpiles as well as smuggling of horn out of the country. These acts would tarnish South Africa’s reputation with CITES Parties and could jeopardise future attempts to legalise international trade in rhino horn.”

However, the trust that such ‘compliance’ is achievable and beyond future corruption remains fragile, but regardless, illicit activity will perpetuate as long as there is demand:

“As it stands now, South Africa lacks the conservation management and law enforcement systems to manage domestic trade without corruption playing a role or domestic and foreign illicit trade systems penetrating it” – page 210, “Fluid interfaces between flows of rhino horn,” GLOBAL CRIME, 2017, VOL. 18, NO. 3, 198 – 217

The DEA’s draft regulations for ‘domestic’ trade in rhino horn that were rushed out for ‘comment’ in February 2017 are still to be implemented, but the DEA still has many questions to answer:

- Where is the independent, peer reviewed science that shows ‘domestic’ trade will not in all likelihood, be detrimental the species (and the DEA is not placing unfounded faith in compliance)?

- “Who did the minister consult in drawing up the draft regulations and how did she arrive at a figure of two horns per person?

- How will an already stretched and under-funded regulatory and policing force cope with monitoring internal trade?

- How will she ensure that the horns will not enter the illegal international markets?

- And is this the first step towards South Africa putting forward a proposal for full international trade in rhino horn at the next CITES conference in 2019?“

“Op-Ed: South Africa opens the door to the sale of wildlife parts,” Daily Maverick, Don Pinnock, 5 September 2017

The impasse with regard to the DEA’s stance and potential ambition to obtain international trade in rhino horn is also undermining demand reduction efforts in Vietnam, as Breaking the Brand highlights:

“In speaking to several people working on the rhino horn demand problem, locally in Viet Nam in October 2014, BTB was told that South Africa’s pro-trade/no-trade debate was the key thing slowing the Vietnamese Government’s response to tackling consumption of rhino horn in Viet Nam.

Why would any government target its high net worth citizens, who are the primary users of genuine rhino horn, when:

1. These are the business people and entrepreneurs driving Viet Nam’s rapid economic growth; and

2. What they are doing could be made legal in 2019 if the South African Government decides [and receives CITES Parties’ blessing at CoP18] to take the pro-trade route.

As people stated, the pro-trade debate in South Africa effectively neutralises law enforcement based success in Viet Nam.”

If the true altruistic intent is to end the poaching of rhino, then ‘trade’ is not the answer:

“Our model indicates that less conventional demand management strategies (such as consumer education, behaviour modification), appear to be more effective strategies in managing rhino horn demand than legalising the trade in rhino horns – “Debunking the myth that a legal trade will solve the rhino crisis: A system dynamics model for market demand,” D. J. Crooks and J. N. Bilgnault, Journal for Nature Conservation, Elsevier, Pretoria, 2015

Dr George Hughes acknowledged that several opponents of legalised rhino trade are unlikely to be persuaded by the pro-trade ‘arguments:’

“It is a bit like trying to persuade a person who is deeply religious to give up their beliefs … but right now we are on a roller coaster ride to the near extinction of the rhino in the near future. A perfectly legal trade has to be tried” – “Rhino baron should be hailed, not pilloried says former parks boss,” Times Live, 30 August 2017

I would suggest trying to encourage those wedded to the failed theory of ‘sustainable wildlife utilisation’ and their faith in simplistic economics is indeed “like trying to persuade a person who is deeply religious to give up their beliefs…” and no, a legal trade does not have to be risked/”tried” when the likely potential negative outcomes are analysed using impartial science and rationality.

Further Reading

“Dear John, Our response to your rhino horn auction,” Dr Simon Morgan (co-founder of Wildlife ACT), 22 August 2017

“Why legalizing any trade in rhino horn is bad for rhinos,” Steve Galster, Freeland, 22 August 2017

“Is John Hume dealing with criminal syndicates in auctioning his rhino horn?“ EIA, 23 August 2017

Bibliography:

“The Horn of Contention,” Economists at Large & International Fund for Animal Welfare, November 2013

“In conclusion, economic logic does not suggest that a legal trade in rhino horn would necessarily reduce poaching of rhino in Africa. Under certain conditions this may occur, but there is little empirical evidence cited in these papers to suggest that these conditions are currently in place.”

“Fluid interfaces between flows of rhino horn,” Annette Hubschle, Institute for Safety Governance and Criminology at the University of Cape Town (UCT), GLOBAL CRIME, 2017, VOL. 18, NO. 3, 198–217

“As it stands now, South Africa lacks the conservation management and law enforcement systems to manage domestic trade without corruption playing a role or domestic and foreign illicit trade systems penetrating it.”

“Operation Red Cloud – Grinding Rhino Horn,” 18 July 2017, Elephant Action League –

“EAL’s feeling that legalizing trade is likely to collapse international attempts to protect rhinos.”

“Tipping Point – The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime,” Julian Rademeyer, 2016

“A Game of Horns,” Annette Michaela Hubschle, International Marx Plank Research School on the Social and Political Constitution of the Economy (IMPRS SPCE), Köln, Germany, 2016

“To stop poaching, ivory ban must be permanent,” Ross Harvey (MPhil), Elsevier, 2016

“Debunking the myth that a legal trade will solve the rhino crisis: A system dynamics model for market demand,” D. J. Crooks and J. N. Bilgnault, Journal for Nature Conservation, Elsevier, Pretoria, 2015

“….we find that a legal trade [in rhino horn] will increase profitability, but not the conservation of rhino populations.”

“Leonardo’s Sailors: A review of the Economic Analysis of Wildlife Trade,” A. Nadal and F. Aguayo, The Leverhulme Centre for the Study of Value, Manchester, 2014

“The pro-market argument starts from the premise that poaching and illegal trade are a consequence of trade bans imposed by bodies like CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora).”

“One of the most striking features in the economic analysis of wildlife trade is the level of misinformation concerning the evolution of market theory over the last six decades. To anyone who comes in contact with the corpus of literature on wildlife trade, and in particular the literature recommending the use of market-based policies, the uncritical use of theoretically discredited analytical instruments is a striking revelation. Perhaps the most important issue here is the conviction that markets behave as self-regulating mechanisms that smoothly lead to equilibrium allocations and therefore to economic efficiency. This belief is not sustained by any theoretical result, a fact that is well known in the discipline since at least the early seventies.”

“Pointless – A quantitative assessment of supply and demand in rhino horn and a case against trade,” NABU International, Berlin, 2016

“These simple calculations support the notion that lifting the ban on commercial trade in rhino horn is likely to facilitate the extinction of rhinos, rather than support their survival. Illegal rhino horn trade is an international problem that requires a well-coordinated global response comprising a genuine commitment to strong legislation, uncompromising enforcement and creative demand reduction initiatives.”

“The Conservation Cost of Game Ranching,” A journal for the Society of Conservation Biology, Balme et al., 26 July 2016

“Breaking the Brand – 3rd Annual Report,” Breaking the Brand, 2017

“The question of the legalisation of the trade in rhino horn is immensely complex AND involves a massive downside risk – the risk of rhino extinction in the wild if the pro-trade strategy is flawed, which Breaking The Brand believes to be the case.”